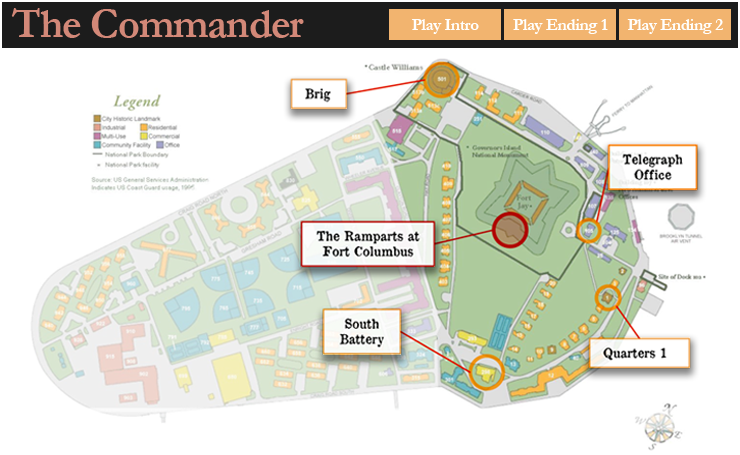

Click a location name on the map to hear the corresponding audio or read the complete text in chronological order below.

Prologue

In December 1860, with the authorities of South Carolina moving closer and closer to succession, the federal troops stationed at Charleston took possession of the newly made and highly defensible Fort Sumter, in the center of the harbor. Unfortunately, the Fort was gravely under-supplied and under-manned. The Buchanan administration, not wanting to further provoke hostilities, decided against sending a warship to relieve the Fort, and instead commissioned an unarmed commercial vessel to bring new troops and supplies.

Preparations were made and on January 5th, 1861, a force of 200 men, under the command of U.S. Army Lieutenant Charles R. Wood, was to board the steamer Star of the West at Governors Island, scheduled to set out for Charleston at 5:00 that evening.

At 1:00 that afternoon by telegraph from Washington, that order was reversed. But would that news reach Lieutenant Wood in time…

Intro

January 5th, 1861. You are Major Theophilus H. Holmes, Commander of Fort Columbus, Governors Island. A native of North Carolina, you are a veteran of the Indian Wars in Florida, and the Mexican-American War, where your promotion at the Battle of Monterrey was due to Jefferson Davis witnessing your courageous actions.

South Battery: 1:30PM

A fellow named Darnton—one of the Signalman for the base—presented me with General Scott’s cable at the South Battery. The import of the order that the ship should not deploy struck me at once. If The Star of West sailed under these heavy batteries and was sunk, the resulting outcry must create at last a public division between the Union and Confederate states, and with such confident violence that Washington would not dispute the separation. Such was the opportunity presented to me, without warning. Dare I seize the chance? Dare I be the one to set in motion actions that would ensure the Southern states would secede? I took the Signalman, who smelt unpleasantly of gin, into the chart room, asking the number of other persons who knew of this cable. He assured me the number was zero. This negative answer made my decision.

Quarters no. 1: 2:00PM

I quickly composed a message, sealed it with wax, and announced that Darnton should deliver it to Quarters 1, my private residence. To the man’s protestations – that non-commissioned ratings were not allowed in Nolan Park – I assured him he only needed to present the sentries with his letter, and all would be well. Of course, I had called to mind the stratagem from Hamlet, and as the Prince sent messengers to England bearing their own death warrants, so the letter the dull-witted Signalman carried was nothing more than an order for his immediate arrest and detention. Once Darnton departed the Battery I took careful stock of the three officers around me, driving them to their tasks. Not one of them suspected a thing.

Telegraph Office: 2:51PM

The minutes passed slowly in the Battery as I waited relief from Captain Heintzelman, who I deemed above all others must have no knowledge of the order not to sail. Despite my confidence in my action – indeed, in the divine providence of the opportunity – I felt a doubt gnaw upon my mind. What if Darnton had left a record of General Scott’s cable in the telegraph office log – indeed, what if his original transcription of the cipher lay there for the next signalman on duty to discover and decode? Displaying no outward concern, I at once I made my way to the Telegraph Office. Darnton’s relief had not yet arrived, and I was able to search thoroughly, a good 9 minutes by the clock, yet no trace of the original cipher did I find. At least I could make certain that no further cable would arrive. Once outside I locked the door and ordered two passing soldiers to stand guard. No one was to enter the Telegraph Office under any circumstances without my command.

Brig: 4:30PM

A brief visit to the wharf, to wish Lt. Wood a successful voyage, confirmed that the order Darnton delivered to me had not reached the ship, satisfying my worries. She would set out in only thirty minutes more. On my return, however, I saw a woman passing near Quarters 1 and recognized her as my own servant, Amelia Darnton, the Signalman’s wife. I followed as she continued on to the South Battery, where I knew she could not pass. Yet my prudence got the better of my doubt, and seeing we were alone on the doorstep I called out to the woman. With just a single look at her eyes I knew she had been informed of the entire tale. Seizing control, as if she had been any wavering soldier under fire, I told her in direct terms that if she desired her husband’s freedom, she must say nothing of the cable until The Star of the West had sailed – and to do otherwise would be his utter ruin. I sent her off and then my own nerves got the better of me. I made my way to the Brig only to find the Signalman had been freed by Heintzelman, the Captain. Recalling the flag codes I had seen at the telegraph office, I rushed at once to Fort Jay to signal the vessel to depart as planned.

Ramparts of Fort Columbus: 5:01PM

I stood on the rampart watching the flags I myself had hoisted flutter tautly in the stiff January wind. I hoped, no prayed, that the decision I had made was the right one and that the lives of those men aboard the Star of the West would be safe in any case. The die was cast now and I had played my part at the beginning of what was clearly destined to be an episode critical to the life, or the demise, of this great country.